Japanese Urban Fantasy and the Social Terrain of the Early Digital Age, Part 1

This post is the first of two halves of a book-length post titled Japanese Urban Fantasy and the Social Terrain of the Early Digital Age. The second half can be found here.

In addition, feel free to read the whole post as an book in epub format.

This post will contain moderate spoilers for Kinoko Nasu’s major works (Mahou Tsukai no Yoru, Kara no Kyoukai, Tsukihime (the original), and Fate/stay night). Other novels and such are addressed in passing but do not warrant a spoiler warning. However, since it is a mystery novel, I will warn readers of a brief discussion relating to the narration style of The Decagon House Murders by Yukito Ayatsuji. In addition, a major element from a certain Natsuhiko Kyougoku mystery novel is discussed, however the title is intentionally withheld so as to not spoil which one.

Table of contents

- Part 1: The rise of Kinoko Nasu: A cultural autopsy

- Part 2: After Nasu: The consumption of myth as data

The cultural relevance of Kinoko Nasu is more or less self-evident. This much can be demonstrated with three words: “Fate/Grand Order.” This game has solidified its place in the top ten highest grossing mobile games of all time and is a consistent juggernaut in the games-as-service space. The intellectual property of Type-Moon stands far above all comparable peers from the world of visual novels; it plays its cards at a big-boy table of entertainment capitalism, rubbing shoulders with the mass scale AAA products of Tencent, Epic Games, and Nintendo. This is a remarkable reality. After all, for all of the institutionalisation of Fate/ as a mass market brand, it is also a brand that is seen as synonymous with the work of a single Japanese novelist who started self-publishing his work during the post-crash decade of the 1990s. It straddles the line between independent and AAA with remarkable ease.

However, this feel-good story of overcoming and self-made success is not the object of our attention for today. There are other places that catalogue the fairy tale-like biography of Kinoko Nasu and Type-Moon. Rather, the question before us is an analytical one: At one locus point of his career, Kinoko Nasu was writing novels for his friends with only modest aspirations for the future. At the other, Nasu became the creator of a massive intellectual property that practically prints money. There is a need to connect the dots and explain what happened—but not in terms of economics and market share. Rather, the Nasu phenomenon needs to be clearly discussed in terms of literature and culture. A theory needs to be developed that explains the origins and character of his writing outside of the general rise of anime in the 21st century imagination.

Let us put this another way: We know that Kinoko Nasu matters to people because his works sell so well—and because of the scale of the conversation these works generate. Of course, this mass attention is not necessarily synonymous with artistic value. We can only say that his works matter with this kind of dispassionate neutrality, and not that they deserve to matter. However, we should not busy ourselves with fussing over the question of his ‘value’ in that sense, as there is a large body of critical work that discusses the merits of each of Nasu’s works in isolation. We are not here to repeat those debates. Instead, we are here to situate Nasu’s cultural importance apart from his critical value—that is, apart from judgments of ‘good’ and ‘bad’. There are two questions I wish to tackle contained within this demand:

- What is the literary history and texture that ties Nasu’s various works together? That is, what is the content in terms of movements and genres that makes something a “Nasu-like” story?

- Why have imitators not yet succeeded in reproducing this genre content in the form of a comparably popular subgenre of Nasu-likes? Or, put another way, why has Nasu’s style remained so intimately associated with him, rather than developing into a broader phenomenon?

In combination, the answers to these questions will sketch out a useful theory for Nasu’s work from the perspective of culture, without relying on the broader economic tale of the rise of anime and anime-like media markets. Not to say that those factors are irrelevant at all. It is simply that they are outside the scope of this post.

These questions can be understood a little differently if we cut right to the chase and do some history. In the third volume (July 2004) of Faust (a literary magazine operated by Kodansha), the main feature editorial provocatively declared that The “Shindenki” Movement Starts Now! While many Japanese genre terms such as isekai or shounen are widely known even in the West, I expect that the term shindenki is new to many readers. However, the term was also new to Japanese readers of Faust at the time—this is what made the claim so provocative. The magazine claimed to be launching a new genre at that very moment. The editorial further clarified that:

The present moment of the 2000s is one where the extraordinary content of the past has fused with our ordinary daily lives … One answer is the denki novel, which is a format that expertly depicts the extraordinary as part of the everyday … Based on this understanding, Faust has developed a “new (shin) denki” novel tradition that fuses the denki movement of the 1980s with the anime, manga, and video games of the 1990s.

Faust (Kodansha) would carry through with this promise less than a month later in August 2004, publishing what was promised to be the first shindenki novel ever available to mass audiences. This novel was the first volume of Kara no Kyoukai: The Garden of Sinners by Kinoko Nasu. To be clear, Kara no Kyoukai had originally been self-published by Nasu back in 1998, so any promise of novelty was inherently deceptive. However, a major publisher picking up a self-published novel was definitely of note in 2004—this was before the narou-kei boom, Fifty Shades of Grey, and the current web novel market. And Faust was making a big bet with Kara no Kyoukai. They had declared it to be the spearhead of a brand-new market-defining genre known as shindenki. And they positioned Nasu as the leading author whose style would define this new genre. 2004 was also the year that Nasu’s doujin circle known as Type-Moon had incorporated as Notes Co. Limited and released the massively popular work Fate/stay night, that Nasu is still known for to this day.

We will return to the word denki as it is used in the earlier quote, and further defining what exactly Faust intended by the neologism shindenki, once we get into the meat and potatoes of this post. But the conclusion of this story is that Faust was simultaneously proven extremely correct and extremely incorrect. The style of Nasu did capture audiences—beyond the scale that Faust could have ever imagined. Kara no Kyoukai made a splash upon release. Fate/stay night went from strength to strength. And from the close of the decade onwards, as both titles received extremely popular anime adaptations by Ufotable, and as the mobile game Fate/Grand Order sold like hotcakes, Nasu’s intellectual property grew into a titan of the industry that dwarfed all competition. However, the boom in other shindenki writers that Faust was relying on never came. Whatever appeal they saw in Nasu proved to be prophetic, but the other attempts to reproduce that appeal met modest success at best.

Therefore, a large portion of this post will be an analysis of Nasu with a mind to discovering the exact contents of the literary force that Faust believed that he would embody—and why the Nasu phenomenon was ultimately sui generis. That is, we are going to break down this part prophecy and part miscalculation. Whatever Faust saw in the conceptual framework of shindenki arrived with Nasu, but it failed to do so through any of the other vehicles arranged for it. This is why an analysis of Nasu with an eye towards answering our original questions will more or less take the form of a history of the literary merit of shindenki throughout the timeline of his career.

Chapter 1 – Denki: How we invent the past

To the beginning

Of course, as Faust’s feature hints at, the story of denki fiction goes back before Nasu’s career—at least as far back as the 1980s. However, for the portrait we intend to paint, we have to expand our time horizons quite a touch more than that. We are going right back. And by ‘back’, I do not mean by a few decades—I mean China in the 7th century.

The entire history of Chinese literature is something that we cannot and will not summarise in this post. However, to start with some familiar ground, I will assume that most readers are at least familiar with the reputation of the Romance of the Three Kingdoms. Originally written in the 14th century, the Romance is a dramatic telling of the titular conflict of the Three Kingdoms at the close of the Han dynasty (2nd and 3rd century). It is one of the great novels of classic Chinese literature and is understandably the frequent object of literary analysis. However, the distinguishing feature that interests us today is how the Romance mixes real history with fantastical fiction.

This end point—dramatic retellings of historical epics that add fantastical elements—evolved from centuries of Chinese literary traditions. The rough chronology goes something like this: The essential tropes, conventions, and lore of Chinese fantasy fiction had their origins in Chinese mythology. Due to the early adoption of writing in China, we can easily trace how this mythological canon was codified and coalesced around particular ideas. An important strain that formed from this was so-called “xia” fiction—xia meaning hero or warrior in Chinese. Some important sub-categories of this story type were wuxia (martial hero) stories, which can be found in much of the lexicon of modern martial arts fiction, and xianxia (immortal hero) stories, which combined stories of heroics with a magical path to immortal enlightenment (cultivation) based on Taoist mythology. Variations on these kinds of stories can be found in the literature going back to the earliest dynasties of Chinese history.

Historical literature was also present from an early period in China. While some attempted sober, fact-based record keeping, the mixing of history with myth was also commonplace—just like in almost all contemporaneous civilisations. History was communicated through narrative, and sometimes exaggerated or mythologised any real events contained within. Of course, this is nothing unique to China; from the Iliad to Arthurian legends, historical settings are often mixed with mythology in classical literature. But the nuances of the development of Chinese literature are decisively more important than comparable trends in the West when it comes to the particular strain of Japanese literature we are here to discuss. Regardless, the conventions of the fictional xia stories and the expected mythological canon to be found in historical stories overlapped and intermingled with ease.

The dominant styles of this intermingling became definitional to the various movements or phases within the development of popular Chinese fantasy fiction. For example, zhiguai literature, which reigned between the 3rd and 7th century, was dominated by highly objective, prosaically direct descriptions of a mix of myth and history. As Robert Ford Campany, a leading scholar on early Chinese literature explains:

[Zhiguai] are written in mostly non-metrical or loosely metrical but non-parallel, non-rhyming, classical prose. They are thus distinct on the one hand from various early combinations of prose and verse, from fu (“rhapsodies”) and other poetic forms, and on the other hand from later-developing styles of prose that prominently incorporated vernacular forms.

The next development to come was, naturally, the “styles of prose that prominently incorporated vernacular forms” alluded to by Campany. This was gradually incorporated into chuanqi literature, which evolved out of zhiguai literature from the 7th century onwards. Of course, the division between these phases is vaguer than this timeline implies. Stories in the style of the zhiguai era continued to be popular long after the 7th century. And both zhiguai and chuanqi stories were often collected together and considered to be part of the same fundamental genres of myth and folk literature. However, the chuanqi era generally contained many distinct and important innovations compared to what could be found in the zhiguai era. Characterful first-person narration started to appear, and the plots were sometimes structured around accommodating this new stylistic flourish. Common forms for the chuanqi story included a bureaucrat or minor official witnessing a fantastical and historically significant event first-hand, or a third party recounting a tale they were told of this event in the style of a rumour or myth. However, beyond these stylistic evolutions, zhiguai and chuanqi often approached the presence of the supernatural with a shared understanding. As explained by Campany:

Texts of this genre have as their clear and primary focus phenomena that are in some sense (and with respect to some boundary and set of expectations) anomalous … in fact, the juxtaposition of the ‘ordinary’ and the ‘extraordinary’ is a key poetic device of anomaly accounts.

Where this development becomes keenly important for our understanding will become self-evident when we consider a certain linguistic fact: The Chinese characters for chuanqi, when read in Japanese, form the word denki—they are the same word. What Faust referenced as “the denki movement of the 1980s” was an explicit revival of stories that emulated the chuanqi phase of Chinese literary development. In order to understand what authors thought they were reviving in this era; we should summarise the history we have covered thus far:

Throughout the centuries of Chinese literary history that led to well-known classics such as the Romance of the Three Kingdoms, history and myth intermingled and developed into a shared canon and setting for the whole genre. This canon is typified and codified in the conventions of fantasy fiction such as wuxia stories. Furthermore, this general form of Chinese historical fantasy went through various phases where particular stylistic flourishes became dominant. According to Campany, a dominating trend in the early Middle Ages was “the juxtaposition of the ‘ordinary’ and the ‘extraordinary’ [as] a key poetic device.” Furthermore, in the chuanqi phase—which we will refer to as denki from now on for clarity—that came into definition from the 7th century onwards, stories that dealt with these subjects included more stylistic prose and characterful narrative devices such as perspective and subjectivity. Sometime around the 1980s, there was a denki movement in Japan that reproduced elements of this much earlier movement from China. And in a 2004 editorial, the Japanese magazine Faust declared the beginning of a “new denki” movement, with Kinoko Nasu as its leading author. This more or less accounts for the historical outline given thus far.

The emergence of modern mythology

Naturally, we need to take a closer look at this denki movement of the 1980s. Why would a millennium-old style of Chinese fantasy story have any purchase in the Japan of the 1980s? And how does this relate to the fiction of Kinoko Nasu? Kazuhiko Komatsu and Masatoshi Naitou described the impetus for the movement like so:

To summarise, denki exists to depict the “strangeness” in society. “Strangeness” refers to things that are rare, inexplicable, supernatural, or abnormal. To go further, denki explores the strangeness on the exterior or periphery of the everyday world. In highly industrialised, regulated societies, the homogenisation of experience does not leave much cause to encounter strangeness in everyday life. Such a society lacks imagination. Therefore, people reach for opportunities to enliven their everyday life and imagination through this strangeness.

Although this description is in reference to the denki fiction of Japan in the 1980s, the parallels to the earlier characterisation of denki fiction in historical China are so blatant that they do not need repeating. We should instead focus on the points of departure between the two. Where the original denki literature was imbued with the aesthetics of timeless myth and historical epics, the denki fiction of the 1980s responded to “highly industrialised, regulated societies” and “the homogenisation of experience.” Leaving the particular causes of these feelings aside for the moment, this simply means that we must recognise the context of pre-modern, pre-capitalist Chinese literature as distinct from the meaning of a revival of similar literature in capitalist post-war Japan. A brief historical stroll should reveal this context.

Just as it has its roots in the Chinese original, the development of Japanese denki fiction developed under the shadow of an existing history of Japanese myth and folk-legend that formed a canonical tradition of fantasy fiction. However, as Walter Benjamin said, “history is the subject of a structure whose site is not homogeneous, empty time, but time filled by the presence of the now:” Denki fiction cannot be understood as the culmination of the unfolding of the eternal past. Instead, its lineage materialised as a reproduction of the past from the perspective of its present imagination. To investigate this imagination, we must start with Kunio Yanagita, who codified much of Japan’s modern folklore and fantasy.

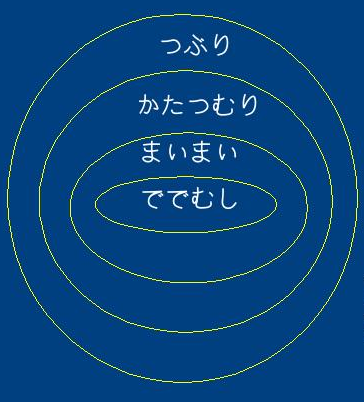

Kunio Yanagita was a Japanese folklore expert and scholar who was most active throughout the early 20th century. Beyond just collecting folk tales, Yanagita wrote highly influential analyses on their cultural origins and meanings. In his 1930 work, On Snails, Yanagita developed his theory of the dialects of the centre and periphery. According to this theory, while culture and language would develop first in cultural centres, they would also subsequently ripple out to periphery communities over time. The result was that particular linguistic and cultural practices would form something of a geological strata system, where culture and language would go backwards in time in proportion to the community’s distance from the centre. Yanagita relied on the titular example of snails, and presented the following model for the prevalence of the concept’s different synonyms depending on one’s distance from the centre of Japanese culture:

The centre of Japanese culture was effectively equivalent to Tokyo in this case, but other examples included notable urban centres such as Nagoya and Kyoto. The sheer simplicity of this theory ensured that it obtained a certain superficial validity through its limited falsifiability. In much the same way as various dialects of French could be visualised through their distance from Paris, Yanagita explained the dialects of Japan through their distance from Tokyo.

In its day, On Snails and Yanagita’s theories were remarkably popular. And through his other work as a folklore expert, many popular depictions of Japanese history came to be shaped by this contrast between the imperial, urban centre versus the provincial interests of the periphery. The theories of Yanagita are just one influential anecdote of how a particular imaginary version of Japanese history came to be embodied in a mythic historiography rooted in the 20th century.

The first half of this century saw the arrival of Japan as an imperial and colonial power across East Asia. In the wake of the Meiji Restoration, Japan’s history of decentralised shogunates gave way to a highly militarised, centralised, and Westernised imperial state. When each generation looks into the past, they will inevitably imagine it in the shape of a narrative that explains their present. In this sense, a theory such as Yanagita’s that explained the peripheral subcultures of Japan in terms of their relationship to the centre of imperial authority, arrived at precisely the right moment. The dictatorial emperor that ruled using the Meiji constitution was technically a recent phenomenon, invented by the structural features of the Western-style absolute state. While there was a long history of a nominal imperial family, political power in Japan had always been shared with the shogunate military government and the various decentralised power centres. However, the assertion of a new kind of imperial authority was retroactively legitimated as a continuation of the 1000-year-old history of the Japanese ‘centre’ that ruled over the various ‘periphery’ peoples of the Japanese islands. As Noriko T. Reider says of the developments in the Meiji period:

Japan’s hierarchical system goes beyond this world. The system is applied to the realm of the supernatural, or one might say that the hierarchical order of the supernatural world has always been reflected in this world. In modern Japan, the emperor’s supernatural status was publicly asserted, and with the imperial court once again at its center, the status of various supernatural beings was (re)examined; some were affirmed and others were simply dropped from the cosmic map.

It was a naked display of retroactive nation building comparable to the contemporaneous inventions of Italy and Germany. Prior to the French Revolution and intervention of Napoleon Bonaparte, what we now think of as Italy and Germany were a patchwork of separate states with limited cultural intimacy. However, in response to the military threat of Napoleon, and to the Revolution’s radical idea of a brotherhood of all men, the relationship between the so-called ‘nation’ and the state became a pressing political subject. States could no longer legitimate themselves on the same terms: they needed a new tradition as the authority for a ‘national people’ in order to justify their own existence. The status quo where a ‘German’ could have one set of rights in Bavaria and yet another in Hanover could not be reconciled with this new ideological agenda, and so the political project of a pan-German state was rapidly incepted.

This is all to say that the nations that emerged in the modern era of the French Revolution were in many ways disconnected from their pre-Revolutionary antecedents. It is as though Napoleon killed the old states of Europe, which were premised on the divine rights of kings, and placed the Romantic ideal of the nation, premised on the decidedly secular rights of the people in general, into their zombified corpses to wander about ever since.

However, at any given moment, history is the art of using the past as a mirror to see the present. And since it can be so difficult for people to notice the concrete operation of vague historical forces, a new mythological history has to meet the moment and explain the present in terms of comprehensible narratives and personalities. This is a general pattern; smaller scale ideas are able to remain in their pure form as esoteric theology, but for ideas to rise up and capture the mass culture of a society, they have to transform into a personality-driven myth or legend. This logic is easy enough to recognise in the oldest traditions of myth: The vague mysteries of the sea were embodied in the myth of Poseidon, and the legend of King Arthur was invented in order to personify the ambiguous and gradual reconciliation of a shared ‘British’ history among the various peoples that occupied the British Isles after the Norman conquest. In much the same way, the historical forces that acted on states in the modern era were reduced down to easy-to-understand personalities and narratives for mass consumption.

During the modern era, the mythologisation of political forces has often taken the form of stories about secret societies and international conspiracies. Some, such as the philosopher Hannah Arendt, have drawn a direct connection between these stories and the maturation of modern antisemitism as manifested in 20th century fascism. How deeply entrenched such stories remain is easy to see in the myth of Nathan Rothschild and the Battle of Waterloo.

The myth, as told in popular culture, is that the Jewish banker family of the Rothschilds spread a false rumour that Napoleon had won the battle of Waterloo all across London. Meanwhile, Nathan Rothschild, who is alleged to have been the first in London to learn of Napoleon’s actual defeat, profited immensely from the resultant market panic. Indeed, the most pernicious versions of the legend allege that Napoleon’s defeat was itself engineered by the Rothschilds for the sake of this manoeuvre. However, this story is a total myth. The historian Niall Ferguson attributes this urban legend to the immensely popular Honoré de Balzac and his short story La Maison Nucingen, which repeats a similar tale. In this way, the innumerable and intangible historical forces that led to the sudden defeat of the seemingly insurmountable Napoleon were explained as the actions of a secret cabal of Jewish bankers.

For his part, Balzac—perhaps the most important of the European novelists of the Romantic era—played an immense role in establishing the mythology of this new European world. In his History of the Thirteen, he depicted a secret society of thirteen families that control all Parisian political affairs. This morphed over time into the ‘thirteen families’ of the Illuminati that are present in all manner of contemporary conspiracy theories. And much of the most popular literature of the period is positively bursting with references to secret cults, Free Masons, cabals of the wealthy, and other similar concepts. Just as ancient man explained the whimsical forces of nature by way of Poseidon or Zeus, modern economic forces are explained with sinister cabals and secret societies. It is fundamentally the same process—the art of creating a personally comprehensible mythic past to justify the present. And just as Europe had to reinvent this past during its modernisation, Japan found itself subject to this same process during its imperial modernisation. That is, the period from the Meiji Restoration until the collapse of this imperial system at the hands of the United States during the Second World War.

Let us return to the question of snails. The historical task of Kunio Yanagita, whether he was aware of it or otherwise, was to codify the folklore and history of Japan in such a way that it explained the new imperial system that Japan found itself under during this period. In many ways, Yanagita and his contemporaries were developing a mythology that was the exact inverse of its European parallels, even as it had a fundamentally similar role. In post-Revolutionary Europe, the mythology we have discussed thus far existed to explain why the ruling class still held on to political power despite the emerging consciousness of ‘national peoples’ that believed in their own self-determination. In other words, it was explaining the precarious position of the European aristocracy, which was soon to be overthrown in the bourgeois revolutions of the 19th century. In Japan, power had flowed in the exact opposite direction. The decentralised power of feudal Japan had been centralised in the Tokyo government and the emperor, who was believed to be the embodiment of literal divine power. Therefore, a new mythology was needed to explain why the old power structure of the periphery should accept the legitimacy of the central government. The historical contrast between the centre versus the periphery, where the periphery had a natural purpose but was ultimately subservient to the centre, was essential to this legitimating myth.

After the war

However, these pre-war developments are not quite enough to understand denki fiction. We need to connect all of this preceding context to the 1980s. As already discussed, the task of building a new mythological foundation for a modern Japanese imperial system produced several canonical ideas. Some, such as the dichotomy between the centre and the periphery, carried an explicitly political purpose. Others are best understood as general revisions to the broad body of Japanese history, culture, and mythology. When studied in the post-war, many of these themes fell under the umbrella of what is known today as ‘Japanese studies’—Nihonjinron.

As already discussed, Japan reimagined itself as part of the modernisation process set off in the Meiji Restoration and the subsequent modern imperial system. However, this reimagining was upended by the end of the imperial system in the Second World War. The prevalence of Japanese studies in the post-imperial era was indicative of how complicated it was to develop a functional Japanese sense of identity in the post-war political settlement. The end of the imperial system necessitated a new Japan and a new mythic history just as the birth of the imperial system had itself demanded. However, the past does not wither away so easily. Some were dissatisfied with the sudden end of the imperial system that had been forced on Japan by foreign military might, and as a result the pre-war era was mythologised and appropriated in the reactionary literature of the post-war period.

No voice represented this conflict of the post-war era quite like Yukio Mishima. Mishima was a reactionary Japanese nationalist and led the vanguard of the right-wing critique of the post-war era. The right-wing critique undertaken by Mishima, and also writers such as Kenzaburou Ooe, made use of the mythic history of the imperial system to frame the perceived degradation of post-war society under capitalism and democracy. The legitimacy of pre-war Japan was explained in the dichotomy between the centre and periphery identified by Kunio Yanagita. While there was tension between the centre, represented by the emperor, and the periphery, represented by minor lords and merchants that ruled over the lands outside of Tokyo, this tension was ultimately productive. In the Mishima vision of things, because the supremacy of the emperor was recognised, the imperial system was able to guide the periphery in the creation of a grand Japanese empire. However, the post-war political settlement inverted this supremacy. The emperor was forced to renounce his divinity, and the capitalist economy enforced on Japan by the United States enriched the petty property holders outside of the centre—that is, the bourgeoisie.

The unifying centre could no longer channel the energies of the periphery towards the enrichment of a unified Japanese national community. Now, under capitalism, the atomised Japanese people pursued their own enrichment with no regard for the project of Japan as a nation. This theory behind the cultural development of the post-war era towards the 1980s was explained by the literary critic Kiyoshi Kasai like so:

Post-war democracy dismantled the vertical differences in the pre-war society, with the emperor at the top, politically and socially. The post-war society, lacking a sense of centrality, can be seen as a mundane hell of uniformity. Yukio Mishima, who wrote The Temple of the Golden Pavilion in the early stages of high economic growth, was aware that post-war capitalism, which economically supports post-war democracy, is the greatest driving force behind the mundane hell of uniformity. Capitalism is a system that dismantles differences and endlessly decentralizes its structure in order to generate profit. Through the post-war reconstruction of the 1950s, the high growth of the 1960s, and the stable growth of the 1970s, Japan’s post-war capitalism reached a new realm called late-capitalism in the 1980s. The indulgence of mass consumer society became a reality.

The high-level capitalist principle (the completed form of the capitalist principle, which profits from the dissolution of differences) transforms the perpendicular differences of a stratified society into the horizontal, level differences of a mass middle-class society. The vigorous capitalism of the 1980s advanced the ‘dissolution of the consumer class,’ making a mass middle-class society a reality. However, the mass middle class of the 1980s was also the perfected hell of mediocrity and assimilation which Yukio Mishima had foreseen. Humans cannot long tolerate the mediocrity of being the same as everyone else.

It was precisely the ‘stratified society’ enforced by the centre versus periphery dichotomy that Mishima lamented the loss of. Under a capitalist economy, anyone on the periphery could be considered equivalent to the emperor so long as they had enough money. The conquest of money, which did not essentially differentiate between people, over the imperial system where the centre was legitimated by mythic history, was equivalent in Mishima’s mind to the death of Japanese history and culture. It was the erasure of ‘the Japanese people’ in favour of ‘a nation filled with Japanese people’, so to speak. On this point, the reactionary Mishima was ironically in agreement with the left-wing radicals of the post-war era, who felt that the sudden collapse of the imperial system through surrender had robbed them of the chance for a decisive communist revolution to overthrow the imperial system at its low point during the war. That is, the communist left also blamed the United States for imposing capitalism on Japan and preventing a communist replacement for the imperial system. Japanese culture in the post-war era was a fierce battle between these left-wing radicals, pro-imperial reactionaries like Mishima, and pro-capitalist liberals.

But I digress; this battle was carried out on the explicit level of politics and high culture. By contrast, denki fiction manifested itself at the level of popular subculture. Put another way, Mishima, who attempted a coup d’état in order to restore the imperial system, and the left-wing radicals who carried out repeated terrorist attacks after 1968 were all explicitly political actors. But there was also a cultural level reaction to the post-war settlement in a sense comparable to Balzac’s development of a literary reaction to the French Revolution—which we discussed earlier. This cultural reaction is where we should locate the denki boom of the 1980s.

The key to this subculture was the gradual ascendency of conscious fiction designed for mass consumption over the ostensibly non-fiction mythologised history of Kunio Yanagita. For example, Hiroyuki Itsuki was contemporaneously writing stories about a secret war between the periphery and the centre even as Yanagita had yet to fully develop his theory of that dichotomy. In the post-war era, ideas from folklore about a secret history of Japan based on this conflict was a fertile theme for fiction that would appeal to those still adjusting to the sudden collapse of the imperial system. At first, this simply meant historical fiction that repeated the tropes and conventions of pre-war mythology—that is, ideas such as ninjas secretly trained out of the reach of the emperor, blood magic, ancient ruling clans descended from those not related to the Yamato ethnicity of the Japanese centre such as burakumin and the ‘mountain people’ (discussed further later). These stories reimagined the imperial system as an era filled with a secret supernatural history, as akin to how the ancient fiction of China had presented history through the lens of myths and legend. By taking the folklore of the pre-war period and using its conventions in a modern genre of fantasy fiction, the denki genre was more or less underway. It already delivered the essential experience as necessitated by the post-war experience, which, as a refresher, was explained by Kazuhiko Komatsu and Masatoshi Naitou who said that:

In highly industrialised, regulated societies, the homogenisation of experience does not leave much cause to encounter strangeness in everyday life. Such a society lacks imagination. Therefore, people reach for opportunities to enliven their everyday life and imagination through this strangeness.

However, the ‘legendary movement’ of denki was more specifically the moment when this genre gained massive popular appeal during the 1980s. This could only happen with the arrival of names such as Ryou Hanmura and Hideyuki Kikuchi with works such as Blood Ties to a Stone and Vampire Hunter D respectively. These works took the crucial step of going beyond the historical period of the imperial system, and also updating these traditional folklore elements with science fiction and fantasy conventions borrowed from Western literature. The result is that the war between the emperor of the centre and the secret societies of the periphery is depicted as continuing in secret in a contemporary setting. In addition, foreign folklore such as werewolves and vampires are mixed in, allowing the structure of a Westernised, capitalist Japan to co-exist with the imperial system of imagination. Once these ideas were adopted, the genre reached a certain kind of maturity. As a result, we could really say that we had a modern denki genre that accomplished three key goals. Firstly, it allowed the imperial system to continue to exist in the imaginations of those who felt the post-war democratic settlement to be too mundane. Secondly, it gained a life of its own in terms of originality, beyond just reproducing older myths and legends, by including updated fantasy and science fiction elements. And lastly, it earned the name denki by focusing on the contrast between the mundane existence of contemporary capitalism and the extraordinary secret war between the centre and periphery.

No work so clearly embodied the era as Hiroshi Aramata’s The Tale of the Teito. Note: this series is usually known in the West by its untranslated name, Teito Monogatari. The word “teito” quite literally refers to the centre in Yanagita’s terms—that is, the imperial palace and the surrounding metropolis. This term specifically means the centre of political power in imperial Japan or China, rather than the capital city in its vague totality. The term’s nuance is comparable to the distinction between the National Mall of Washington D.C. (the area around the White House, Capitol Building, etc.) versus the whole state of D.C., which would include regular citizens with no particular political power in the D.C. suburbs. For our purposes, The Tale of the Centre would be a rather revealing translation, if a bit liberal.

As implied by this title, The Tale of the Teito centres on a fantastical rendition of imperial political power in Tokyo, which continues far beyond its canonical real-life end at the hands of the United States in the Second World War. In comparison to the other major works we have discussed, Aramata is laser focused on developing an alternate supernatural history of the imperial system, rather than busying itself too much with wider Japanese society on the periphery. But its depiction of this centre was highly influential. And the massive success of the series was decisive. Its excavation of older mythological ideas that were largely forgotten by the 1980s reinvigorated mythology in popular culture. In particular, its treatment of the religious practices of Onmyoudou were hugely impactful and can be clearly seen in the work of Natsuhiko Kyougoku and his Onmyouji detective novels. (Kyougoku was one of Kinoko Nasu’s direct inspirations.)

Of particular note, The Tale of the Teito depicts the centre not as the source of stability imagined by nationalists of the pre-war era, but as a chaotic system where outsiders (demons; oni) constantly fight for the right to influence imperial power. Put another way, it modernised the mythology of the imperial system to be comprehensible in the chaos of decentralised post-war democracy. For example, its lead character, Yasunori Katou, is a supernaturally gifted human from the periphery who enters the centre of Tokyo political power and subsequently builds a powerbase for his own objectives. The comparisons to the decentralisation afforded by democracy as contrasted to the imperial system are natural. Such an atmosphere gave its reimagining of politics something of a timeless quality that readers excitedly responded to.

The links between The Tale of the Teito and the wider development of denki fiction are rather stark. For example, according to Noriko T. Reider:

[Aramata] was in constant touch with Kazuhiko Komatsu, an anthropologist. Kazuhiko Komatsu told Aramata about many sources of the strange and mysterious, and Aramata wanted to share that knowledge with general readers as a form of fiction.

We should recall that Komatsu was one of the anthropologists who wrote leading accounts of the nature and purpose of denki fiction. Since it is not our primary topic, we cannot linger too long on the importance of The Tale of the Teito. However, there are key reasons that Reider sees the work, in its reconfiguration of the war of the periphery versus centre, as the key force that distinguished fantasy fiction of this period from the pre-war imagination. According to Reider:

Aramata’s novel, while an entertaining work, is in itself a heterotopic site where its contemporary representations of oni reflect past representations, where oni of the past are not simply superimposed upon the present but where both act as extensions of each other in an odd continuum.

The end of the Second World War brought the collapse of the reconfiguration of the supernatural with Japan’s emperor as its center. World War II made clear to many mainstream Japanese that the branding of oni is arbitrary and could be easily used for war propaganda. While the physical enemies of the Japanese Empire with their oni label may have disappeared, the terrain of the imaginary oni remains rich—one may even say that the Japanese Empire has given more room for the oni to play. The Tale of the Teito is an exemplary work of fiction that utilizes imperial Japan for its backdrop with a sub-theme of the emperor-oni paradigm.

To succinctly summarise the conclusions we should draw from all of this, the ‘legendary movement’ of the 1980s known as denki fiction was at its foundations a trend in fantasy novels that gained mass appeal by explaining the seemingly mundane capitalism of the post-war era in terms of a secret supernatural war—based on a mix of the mythology of the imperial system combined with a dash of Western fantasy tropes. In a barebones sense, it was not that far removed from the logic of how Balzac explained the complex political forces of post-Revolutionary Europe in terms of a simplified narrative of the disputes of a small number of wealthy families. The denki movement just involved magic, ninjas, demons, and the continued power of ancient Japanese authorities, as contrasted with the mundane romance and finance drama of a Balzac story.

Kinoko Nasu enters from stage left

This might all be a bit vague without the tangible experience of reading the novels in question in their particular historical moment, but I now hope we all have a decent idea of what Faust was referencing by invoking the ‘legendary movement’ of denki fiction. Naturally, the next problem is situating Kinoko Nasu into this context. While the denki movement was at its zenith during the middle of the 1980s, from 1989 onwards it went into precipitous decline. The whims of the market and the publishing industry are too chaotic for anyone to truly understand, so it would be impossible to isolate any single reason for this decline. Perhaps the genre was just crowded out by the explosion of interest in Japanese whodunit mystery fiction from 1987 onwards—not to mention otaku culture over the course of the 1990s. Or perhaps the mood of the economic downturn during the 1990s stripped Japan of the mundane feeling that had justified the need for such fantastical works. It is maybe even that the nearly simultaneous death of emperor Hirohito and the end of the Cold War altered Japan’s geopolitical position and sense of self such that there was no longer such interest in the imperial system and the conventions of the pre-war era. Many such theories could be posited, and since these kinds of phenomena tend to be overdetermined, they will tend to lack a single cause.

Regardless, this drastic decline relegated denki fiction to the realm of niche fiction. Even without a single root cause, it was clear that the preceding historical moment had passed, and that the genre would need an update if it wanted to maintain any cultural relevancy. Therefore, the claim that Kinoko Nasu was the vanguard of a new (shin) denki movement is more or less a claim that his fiction has succeeded in bridging this gap. Insomuch as the original appeal of denki fiction was rooted in interest in the imperial system, it was at least clear that reviving interest in the genre would mean moving past nostalgic interest in this system and speaking to the thoroughly capitalist Japan of a generation that does not even remember the war—let alone the pre-war era. A tall task for any writer.

Fortunately, we know how this story ends for the most part, so there is no need for idle speculation. Kinoko Nasu succeeded in capturing—maybe even surpassing—the market relevance of denki fiction. He is one of the most successful Japanese writers of all time, from the perspective of the consumer market. However, the idea of denki and shindenki as a genre beyond him have been left behind in the history books. As we will see when we examine his writing in detail, this is not because he has abandoned the conventions of denki fiction. Quite the opposite, denki fiction still forms the best single framework for understanding his work.

Kinoko Nasu succeeded in the fundamental task that was in front of him. He wrote stories that adapted the model of denki fiction such that they spoke about modern capitalist existence without relying on nostalgic interest in the imperial system. In fact, to go further, he took his stories so far beyond this exclusively Japanese context that they have become a genuine international hit, with overwhelming interest from Western readers. The problem has purely been one of reproduction and variation. His achievement of shindenki—that is, denki adapted for contemporary culture—has become synonymous with himself, and there has been minimal interest in other writers exploring the same topics.

In order to explain this, we need to gain a clearer picture of Kinoko Nasu’s realisation of shindenki. It more or less makes sense to do so by exploring his works chronologically in parallel with his career. However, we will not exactly do so. I would argue that while the majority of his major works are decisively of a shindenki character that moves beyond the particularity of the earlier denki movement, there is one work that occupies a strange point of transition between the two. This work will be most useful for explaining the movement from denki to Nasu’s shindenki. That work is Mahou Tsukai no Yoru: Witch on the Holy Night.

Technically speaking, this will mean that we are progressing through Nasu’s work in a kind of chronological order—at least in one sense. Mahou Tsukai no Yoru was originally written as an unpublished novel in 1996. And while the eventual public release in 2012 was no doubt considerably changed compared to the mysterious original, the core plot nonetheless reflects something of a starting point for his career. But leaving these technicalities aside, our reasons for discussing it first relate more to its content. Namely, we are interested in the way it builds on the ideas of earlier denki writers from the 1980s.

Chapter 2 – Mahou Tsukai no Yoru: Modern-day magic

A fantasy infused with the everyday

In his 1762 work titled The Social Contract, the French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau claimed that “man is born free; and everywhere he is in chains.” This is perhaps the most succinct possible reduction of Rousseau’s general philosophical posture, which was that human beings are a blank slate of good intentions that are subsequently corrupted by the ideological sludge of human society. Rousseau’s line of thought was the foundation for the Romanticist project of locating the pure and naturally good human spirit. In the Revolutionary era that Rousseau influenced, where the concepts of liberty and the brotherhood of all men first became active political subjects, the nature of the individual found itself centre stage. If one could identify the essential character of human beings—that is, how they would act on the basis of their own will, free of the corruption of their peers—it would become possible to understand the ‘true’ will of individuals that we implicitly seek to capture via democratic liberalism.

In the final analysis, Rousseau’s formulation is rather crude. Crude to such a degree that a searing critique can be leveraged at a number of subsequent thinkers who followed in his footsteps precisely for repeating his same mistakes: Rousseau ultimately cannot decide whether human beings in their natural condition are inherently good or inherently a blank slate. Rather, he assumes an equivalence between the two. That is, the results of a pure human spirit are good itself, and society is a precondition to evil. In contrast to this, Hannah Arendt’s formulation of the nature of human beings is much more honest: “Every generation, civilization is invaded by barbarians—we call them ‘children’.”

The difference is not exactly between good or evil—after all, as Arendt also said, “the sad truth of the matter is that most evil is done by people who never made up their minds to be or do either evil or good.” The meaning of a ‘barbarian’ is precisely those who exist outside of an established social order. That is, those who lack the language and cultural context to even understand the meaning of good and evil. The trouble with Rousseau’s formulation, which sees something inherently good in purity and emptiness, is that it wants to find the absolute and essential ‘truth’ of humanity. Humanity does not have a truth because humanity is a process. Lingering on the natural purity of the human spirit is the same as trying to understand a mathematical equation by stopping partway through an addition symbol.

Kinoko Nasu’s Mahou Tsukai no Yoru: Witch on the Holy Night (Mahoyo) is a story that uses such barbarians as a vehicle to explore the consumer-focused Japanese society of the 1980s. However, the issue is not literally Arendt’s barbarians—that is, children; it is exactly Arendt’s point that children mature and assimilate into the context of their society after starting out as blank slates, and that their barbarism disappears before it is even noticed. A much more real complication to the established social order would be if someone truly exterior to society entered into it as an adult, with their own foreign cultural framework fully intact. That is exactly the kind of story that Mahoyo presents.

Soujuurou Shizuki is the archetypal barbarian. Rather than coming from a foreign but ultimately intelligible society—that is, one driven by the same contemporary consumer capitalism as Japan at-large—he was raised in an ascetic mountain community. He is infinitely close to the philosophical ideal of the man raised in the ever-elusive state of nature. And as the instigating catalyst of this story, all of his actions carry the heavy weight of metaphorical meaning. While Mahoyo has no singular perspective character, we should begin our investigation of it by focusing on Soujuurou’s actions and place in the world.

Mahoyo depicts Soujuurou’s sense of alienation and unease as he struggles to adjust to the many conveniences of contemporary Japan. In this sense, the importance of conflict is negated. While conflict is a necessary feature for almost all works of fiction, Soujuurou’s character arc is structured around something more like anti-conflict: Soujuurou’s life in the mountains was a constant struggle, but that struggle moulded his existence such that he never developed independent worries or concerns. The trajectory of his life was remarkably linear. But once he discovered the peace and freedom of contemporary consumer capitalism in the city, Soujuurou’s primary struggle was against his own lack of an individual will. That is, he keenly felt the lack of a clear struggle in the city, as all of his primary needs were provided for. This theme of the unease inherent in peaceful modern existence mirrors a wide range of post-war Japanese literature. For example, from Kenzaburou Ooe’s Our Times:

For Japanese youth, there is no such thing as proactive hope. Hope for us is only an abstract concept. During my childhood, I was surrounded by the war. In those days of adventure and heroic battle, young people could have hope in their eyes and on their lips. Now in its place we are left with mistrust, suspicion, arrogance, and contempt all around us. An age of peace is when lonely men deceive and despise one another.

From this it is easy enough to see how Soujuurou’s sudden transposition from an ascetic lifestyle to an urban existence carries the meaning of a collision between history and the present: Soujuurou comes from a ‘Japan’ before the war—and even from before the Meiji period of industrialisation that produced the corresponding imperial system in the first place. He is the product of long-lost history; it is as though a man from centuries in the past traveled forward in time. And so, his struggle is not a matter of concrete conflict, but precisely the difficulties of adjusting to an era stripped of the conflict that defined his existence until that moment. The juxtaposition between Soujuurou’s (lack of an) interior self as conditioned by this harsh lifestyle versus the light-hearted everyday existence of consumer society forms the metaphorical foundation of the story.

The contours of everyday life are given an unusually central place in Mahoyo, even as compared to Nasu’s other works. While everyday life is important in his other stories, its importance gradually melts away as the dark underbelly of the world comes into sharper relief. Even when everyday life returns, often in a manner associated with nostalgic catharsis for the characters, its meaning has been changed by the adventure itself. Mahoyo is a little different. The action set-pieces are few and far between, and they frame the centrality of Soujuurou’s attempts to build a meaningful everyday existence. The fundamental change that has occurred at the end of the story is that the main cast has gained the ability to value their everyday lives in contrast to their extraordinary origins.

We should hardly be surprised by the importance of the everyday in Mahoyo, nor its corresponding depiction of what Robert Ford Campany referred to as “the juxtaposition of the ‘ordinary’ and the ‘extraordinary’” as present in the earliest Chinese denki fiction. That Mahoyo has a secret world of an extraordinary fantasy setting that is juxtaposed against ordinary life is an informative example of what makes up the core of denki fiction. Denki, in the Chinese sense, was about people from an ordinary world that would be relatable to the reader encountering the strange world of the supernatural and the mythological, which was asserted to be at the centre of history. This same tendency is carried over into the modern sense of the word denki and becomes its defining characteristic. Denki fiction is a subset of fantasy stories where a world that could be our own exists in parallel to a secret world of fantasy. What separates this from more generalised genres, such as magical realism, is the absolutely crucial rule that there must be a way of looking at the setting where it is indistinguishable from our own world. That is, that the story could hypothetically be a non-fictional account of the secret underbelly of reality, only obscured by our mundane perspective as ordinary people.

From dichotomy to trinity

Soujuurou’s background as a mountain ascetic is a clear demonstration of how Nasu’s fiction was influenced by the canonical history of Japan as developed in response to the imperial system. In his 1951 book, Account of the Archaic Hunters, Kunio Yanagita catalogued the existence of the ‘mountain people’ of Miyazaki Prefecture. According to Yanagita, in such remote locations one could find hunter-gatherer communities that were entirely divorced from the contemporaneous cultural and industrial development of Japan. This account became central to the Japanese imagination. For example, the philosopher Koujin Karatani developed a ‘Yanagita Theory’ which used the lifestyle of the mountain people as the basis for a post-Marxian theory of communism. The anthropologist Masao Yamaguchi also emphasised the importance of this account of mountain people in explaining contemporary Japanese culture.

Yet, the presence of the mountain people in the modern mythology of Japan pre-empts even Yanagita’s account. For example, in the 1946 short story The Tale of the Mountain People, Hiroyuki Itsuki depicted a secret tribe of mountain people who are engaged in a generational struggle against the imperial system and the centre of Japanese society. This is all to say that Soujuurou Shizuki’s history and characterisation fits neatly into this lineage in principle. However, as already discussed, Nasu takes the rather progressive step of forcing the mountain people of Mahoyo into the city to confront the contemporary Japanese society that left them behind.

This alteration is representative of how Nasu’s work differs from the traditional centre versus periphery model that situates mountain people as the archetypical outsider community. There is no mention of the emperor in Mahoyo, despite his overwhelming metaphysical presence in earlier denki works. That is, the traditional centre of Tokyo is utterly erased. Instead, the story’s world is structured around the tension between three distinct groups: firstly, the mundane and peaceful capitalism of the city; secondly, the harsh life of the mountain people; thirdly, the secret life of the titular witches.

As already discussed, Soujuurou’s primary adversary is the mundanity and non-differentiation of the capitalist city. In the logic of Mahoyo, the city and its capitalism has become the new centre that the mountain people of the periphery must confront in place of the emperor. The shadow of the imperial system is no longer elevated to the underbelly of society in remembrance of the mythology of the pre-war era. Noticing this reorientation allows us to reinterpret the trinity of forces present in Mahoyo that replaced the centre versus periphery model. It is not just that the centre as the emperor has been replaced by the centre as capitalism, but also that the periphery of rural interests and mountain people (Soujuurou) has been replaced by the new periphery of the secret supernatural (the witches). Mahoyo is a story where Soujuurou, a man out of time, wanders into the conflict between the ordinary and extraordinary of the contemporary era and upends their natural balance. The witches—Aoko Aozaki and Alice Kuonji—initially treat Soujuurou as just a ‘normal person’—as part of the capitalist city that must be kept sharply separate from their life as mages. But over the course of the story, as they come to understand his peculiar position in modern society, they cannot help but accept him.

Beyond its undeniable role as the emotional heart of the story, the dance between everyday life, Soujuurou, and the extraordinary witches takes on a particularly metaphorical importance. One interesting feature of Kinoko Nasu’s writing is how he insists on a very refined ‘coming alive’ of metaphor in the logic of his settings. When discussing Ryuukishi07, I called this tendency ‘poetic narrative layering’, and emphasised its weaknesses in his case. However, to be clear, Nasu’s ability to use this technique is perhaps his greatest strength as a writer—even while Ryuukishi’s failed imitation of it is one of his own greatest failures. Poetic narrative layering is more or less when poetic ideas are reified into material diegetic elements in the story’s worldbuilding, such that characters are constantly forced to discuss the themes of a story insomuch as they engage with its genre conventions. The functioning of magecraft in Kinoko Nasu’s chief setting of the so-called ‘Nasuverse’ makes for an easy-to-understand example of this.

The city and the centre

In the fiction of Kinoko Nasu, magecraft—that is, the activity of mages—is deeply tied up in the diegetic functioning of ‘Mystery’. Mystery is a mechanical function of the world where the understanding that comes with modern society lessens the emergence of new supernatural phenomena. Any supernatural phenomena that are formed in the modern age, where human society has a greater level of understanding, will have a weaker Mystery, and will therefore be less powerful in a crucial sense. The most powerful forces in the world are those that are both secret and ancient—and have therefore retained the highest levels of Mystery. The thematic meaning of Mahoyo is all but plainly stated right there in this metaphor.

The most powerful force in the world is history. But history’s independent power gradually erodes as its mythic meaning is replaced by the development of modern society. The only way that this mythological role for history can be maintained is when we imagine that it operates under the surface, in the periphery of society, away from the prying eyes of contemporary capitalism. Aoko Aozaki and Alice Kuonji are witches, but in contemporary society they cannot live in true isolation. Through their dedication to secrecy, they maintain considerable power. But over time the mundane reality of contemporary society will slowly erase their kind, like the inevitable collapse of a cliff after millions of years at the mercy of the tides.

Mahoyo is set in the last years of the 1980s. That is, at the close of both the denki boom and the bubble economy that stagnated in the 1990s. Modern mages, who live a dual life in the underbelly of contemporary capitalism, enacting their magecraft in secret, are in a constant struggle to maintain the power of the ancient in a world that is constantly evolving. In the climax of this story, the witches believe they have been defeated by the golden werewolf Lugh Beowulf—seemingly the most ancient and powerful Mystery in existence. However, at the last moment, they are saved when Lugh is defeated by Soujuurou Shizuki, as the embodiment of a comparably ancient periphery—namely, the mountain people of denki fiction.

However, Soujuurou’s reasons for doing so are equally salient. Over the course of the story, Soujuurou has changed his posture after living life in the city. He can no longer live a life driven by blind necessity like when he lived in the mountains; with the luxuries afforded by the city, he has started to value his mundane existence and daily life. Yet, ironically, due to his accidental involvement with Aoko and Alice, his daily life overlaps with the secret existence of magecraft. But compared to his existence as a mountain person, the Mystery of magecraft is trivial. Soujuurou repeatedly fails to distinguish between magecraft and the nature of city life, finding them both equally mysterious. Magecraft may be the periphery to the centre of the city, but the mountains are far further afield than either of those and sees them both as the centre: Think back to Kunio Yanagita’s model for the word snail, and its rippling circles.

Nasu’s setting forms a very explicit metaphorical structure that makes it straightforward to understand Mahoyo’s place in the trajectory of denki fiction. Soujuurou, as a representative of the archetypal member of the periphery in denki fiction, enters the city because the growing capitalism of the 1980s transformed the “perpendicular differences of a stratified society into the horizontal, level differences of a combined middle-class society” (Kasai). In this society, the centre is not isolated to Tokyo and the imperial system. It has spread across bourgeois society, to the cities and towns all across Japan. Therefore, the old periphery (Soujuurou) of denki fiction has been captured by the new centre of capitalism and must enter “the mundane hell of uniformity” (also Kasai). From his perspective, this society has no mediation between the periphery and the centre, as both magecraft and modern technology appear as identically alien manifestations of the future that he must confront and conform to.

However, from the perspective of someone like Aoko Aozaki, who was thrown into the world of magecraft after blissfully living a mundane existence under capitalism for so long, the differences could not be starker. To Aoko, who grew up being interested in rock bands and modern culture, magecraft seems far outside the norms of the city, and so she had to resolve to ‘die’ in order to move out to the periphery. And the contrast is even more clear for Alice Kuonji, who is carrying the mantle of a long lineage of ‘fairy tale’ witches known as the Meinsters, and whose magecraft is incompatible with the values of the contemporary world. That these three, who each grew up with such radically different positions in relation to modern society, all form a strange friendship where they co-exist and enjoy a mundane daily life with one another, is representative of how drastically unmediated the world becomes when it is governed by money and consumerism instead of the ancient logic of the imperial system.

The shift from Soujuurou’s old life to this new life in co-existence with both the city and the witches is indicative of what exactly the shift from the values of old denki to Nasu’s shindenki would mean. Rather than Tokyo, the emperor, and the centre of political power, contemporary existence is defined by unmediated city life, consumer culture, and capitalism. And almost no one can truly live outside of this new system; there is no proper periphery. Instead, the periphery of contemporary existence is something closer to the concept of privacy. Therefore, for shindenki, the periphery is a secret life that is distributed throughout the city, as represented by a secret society of supernatural phenomena which is holding on for dear life against the unstoppable might of contemporary capitalism that erases such mythic history with ease.

The story of Mahoyo signposts the last cry of the era of old denki, when the old mythic history of the imperial system still had power. At the close of the 1980s, it was destined to end. Therefore, it makes a great deal of sense that the conclusion of the story has Aoko Aozaki, the witch stuck in her uncertain worry between the past and the present, become the last Magician. That is, she gains power over time via Magic—the ultimate power and greatest Mystery that is obtainable via magecraft in Nasu’s setting. She uses this power to revive Soujuurou (old denki) after he was killed, and to hold power over mythic history.

Chapter 3 – Kara no Kyoukai and Tsukihime: A new century of myth

Urban fantasy and its empty boundaries

As a reminder, Kara no Kyoukai: The Garden of Sinners was advertised by Faust as the first ever shindenki novel. However, by the time Faust declared this achievement, Kara no Kyoukai was technically being sold as a re-print: It had been available on the independent market for several years. The novel was originally self-published (as Nasu’s effective debut) from 1998 to 1999. And while it had been quite successful for an independent novel, Nasu’s self-publishing circle decided to do a spiritual successor that reused elements of the story, except as adapted to the interests of the booming adult game market. As a result, Nasu wrote the visual novel Tsukihime, which was self-published in the year 2000, with two subsequent fan discs released over the course of 2001. Tsukihime also received a spinoff fighting game in the year 2002 and an anime adaptation in the year 2003. This is all to say that by 2004 when Faust declared the beginning of the shindenki movement which was to be spearheaded by Nasu, he had already built a modest company on the back of several shindenki-style stories. Therefore, we actually have a surprising amount of material if we wish to understand what Faust was inspired by when they declared the beginning of shindenki. Between Kara no Kyoukai and Tsukihime, we should be able to establish a reasonably cohesive baseline understanding of what they thought distinguished Nasu’s work from the prior movement.

From a thirty-thousand-foot view, both Kara no Kyoukai and Tsukihime can be described using a lot of the same terminology. In either case, we are talking about urban fantasy stories with hints of mystery and romance; in diegetic terms, both stories are about a protagonist named Shiki who gains the overwhelming power of the Mystic Eyes of Death Perception and is subsequently introduced to the world of the supernatural by a member of the Aozaki family. However, none of these details highlight a particular sense of continuity with the kind of social storytelling we considered in Mahoyo. Given this, we should take a moment to explain the details of each work and their respective connections to cultural history.

Kara no Kyoukai does not function on layered strata comparable to the city-mansion-mountain system present in Mahoyo. And similarly, there are no social outsiders comparable to the barbarian-like Soujuurou Shizuki. City life becomes the natural domain of our characters. And the meaning of that ‘city’ is notably different as compared to Mahoyo. The fictional city in Mahoyo is Misaki, a growing suburban town on the outskirts, representative of the coming universalisation of the city-as-centre over the rural periphery. In Kara no Kyoukai, the setting shifts to Mifune, a dense metropolis located within Tokyo. Put another way, the universalisation of the city has already arrived in Kara no Kyoukai, and everything else exists under it. In Mahoyo, the intermediary between the city and the periphery was embodied in the Kuonji Mansion, which literally existed on the boundary between the two. (As Soujuurou would put it, atop a hill that does not deserve to be called a mountain.) By contrast, the comparable boundary between the normal and exceptional in Kara no Kyoukai is Touko Aozaki’s contracting agency Hollow Shrine. Hollow Shrine operates out of an abandoned shell of a building, and takes on various jobs in detection, architecture, engineering and the like, beyond just supernatural work.

This ‘new’ kind of city is very prominent in the first story of the series, Overlooking View. In Overlooking View, the plot centres on a succession of jumping suicides from the roof of the ‘Fujou building’. Both the Fujou building and Touko’s Hollow Shrine are abandoned buildings that were constructed during the so-called bubble economy of Japan prior to the 1990s. They are the ruins of lost prosperity. It is subsequently revealed that the jumping incidents were due to a kind of haunting, where the disembodied spirit of a woman named Kirie Fujou tempted the young girls to their deaths. It goes without saying that the repeated name of Fujou is not a coincidence, as the building is owned by the ‘Fujou clan’.

The Fujou clan is an ancient lineage of demons (oni) that possess psychic powers. Thinking back to The Tale of Teito reveals the importance of demon clans to the landscape of denki fiction. Demon clans are archetypal of the ancient periphery that fought against the emperor in the model of ancient denki fiction, in much the same way as mountain people. But in Kara no Kyoukai, this periphery has become intermingled with the undifferentiated consumer society of post-war democracy. The same point is repeated in Remaining Sense of Pain, when another descendent of an ancient demon family, Fujino Asagami, goes on a murderous rampage across the city with her mystic eyes. The Ryougi family of the lead character Shiki Ryougi is also an ancient demon clan. However, by the time of Kara no Kyoukai, they have adapted to modern life by taking the form of an urban yakuza gang.

Regardless, returning to the Fujou building for a moment: The Fujou building is a failed real estate project owned by the ancient periphery—that is, by a demon clan. Touko Aozaki—the older sister of Aoko Aozaki who occupied the intermediary position of the Kuonji Mansion in Mahoyo—lives in an abandoned building in the midst of the city. What I intend to highlight with those examples is that the geographical boundary that delineated the social periphery from the social centre in denki fiction has melted away into the boundless structure of the city in Kara no Kyoukai. This is why, insomuch as we recognise the importance of what Kiyoshi Kasai identified as the “perfected hell of mediocrity and assimilation” present in capitalist society, the movement from denki to shindenki is something like the movement from historical fantasy to urban fantasy: Urban existence is a defining feature.

More particularly, each story in Kara no Kyoukai features the collision between everyday city life and the sudden revelation of hidden remnants of the supernatural periphery. Earlier denki stories were centred on the tension between the separate worlds of the periphery and centre. The role of individuals was as a window into these worlds. However, in the undifferentiated geographical space of urban fantasy, the tension between the everyday and the extraordinary runs across the hearts of individuals. This is made most clear in the second story of Kara no Kyoukai, Murder Speculation (Part 1). In Murder Speculation (Part 1), the lead character Mikiya Kokutou is romantically fascinated by Shiki Ryougi. However, his interest inadvertently drives him into the world of the supernatural. At first Shiki seems like the sheltered daughter of the head of a wealthy yakuza gang. However, as Mikiya encounters Shiki’s multiple personalities, ambiguous gender, and seeming connection to a string of mysterious murders, he is forced into the world of the periphery. It is a story about the collision between the everyday and the strange as structured around the boundary point of high school romance.

Inside and out

We should not confuse the rising importance of the contemporary boundless city in Kara no Kyoukai for a total reconfiguration of the denki genre. A natural corollary can be found in the similarly named shinhonkaku genre, which was prevalent in Japanese mystery fiction throughout the 1990s. Just as shindenki was a “new” denki, shinhonkaku was a “new” honkaku: Honkaku here referring to the classical style of puzzle mysteries and whodunits. Shinhonkaku was a neologism coined to refer to renewed interest in these puzzlers after Yukito Ayatsuji’s The Decagon House Murders in 1987. However, even from the beginning there was little agreement on what exactly differentiated this new honkaku movement from prior generations of puzzlers that had existed since the beginning of the 20th century. There were new contextual frameworks and new perspectives that were more prominent in contemporary mysteries when compared to older ones. The younger age of the most popular authors and the particular social mood of the 1990s brought a playful and postmodern feeling to many stories. Yet, there was no absolute measuring stick that one could use to separate out a shinhonkaku story from a ‘regular’ honkaku one. This has made it famously difficult to classify those authors from the shinhonkaku generation whose works adopted a conventional style directed at the mainstream, such as Keigo Higashino. We should approach the idea of a shindenki genre with the same caution and flexibility necessitated by the word shinhonkaku.

This is to say that the distinguishing characteristics of shindenki need not arrive all at once and totally antiquate the idea of a denki story. In this post thus far, we have drawn something of a hard line between denki and shindenki and located it at the debut of Kinoko Nasu. But that framework is a retroactive invention that emerged from Faust. It would be just as accurate to say that shindenki is still just denki, and that denki is slowly becoming more new (shin) with the passage of time.

When Kinoko Nasu’s first visual novel, Tsukihime, was released, it was advertised as a ‘denki adventure’. That this slogan lacks the word shindenki should be self-evident since that word had yet to be coined. However, the willingness to invoke the word denki for a dating sim type game such as Tsukihime also demonstrated the extent to which Nasu’s works did not arrive with a conscious attempt at newness. There was no desire to redefine the terms of the genre. It was simply taken for granted that genres were flexible categorisation tools, with no absolute or essential qualities. While we can easily point to the particularities of the city as a presence in Kara no Kyoukai for a low-resolution definition of shindenki, any comparison to Tsukihime complicates that attempt. If we want to isolate the core orientation of shindenki fiction beyond just a checklist of differences from the preceding denki, Tsukihime is a necessary and illustrative example.

Being set in an expansive and seemingly endless city, Kara no Kyoukai defined itself by the architectural metaphor of urban existence. But Tsukihime offers a slightly different geographical texture. While Kara no Kyoukai was set in the metropolitan Mifune, Tsukihime returns to the same suburban Misaki as Mahoyo. However, the diegetic passage of over a decade has slightly altered its depiction—the germ of a small city has matured into a self-contained urban landscape. The Misaki of Tsukihime has tall hotels, dense apartment buildings, sprawling networks of alleyways; the ever-present visage of the mountains present in Mahoyo has disappeared; the untamed rural road between Misaki and the Kuonji (now Tohno) Mansion has been replaced by a well landscaped modern road. The scope of these architectural transformations become most apparent in the spin-off fighting game, Melty Blood, where Misaki has large skyscrapers that were unimaginable in the setting of Mahoyo.

To be clear, I have described these comparisons in the exactly opposite direction to how they were conceived of in a non-diegetic sense. Mahoyo, which was originally in the form of a decidedly non-visual novel, presumably lacked much of the detail that illustrates these comparisons. It was precisely when Type-moon remade Mahoyo as an illustrated visual novel, with Tsukihime already long out and widely read, that they reimagined the visuals of Misaki in the context of the 1980s and turned back the clock to drain it of its metropolitan sights and sounds. In a similar manner, the recent remake of Tsukihime shifted its own setting to Souya, an urban location within Tokyo comparable to Mifune from Kara no Kyoukai.